How I'll Mark the 30th Anniversary of the 1993 Comstock, Michigan Amtrak Collision

It's a way I never could have imagined.

March 10, 2023, is the 30-year anniversary of the Amtrak crash I survived in Comstock, Michigan. I’ve written about it several times as a way to process the trauma —and heal.

To mark the anniversary, Eric and I plan to ride the Amtrak Wolverine that morning (the same line I rode 30 years ago), leaving from Chicago’s Union Station, bound for Battle Creek, just as I did that morning. We’ll pass over the crash site in Comstock, Michigan, sometime between 10:15am - 10:45am Eastern Standard Time.

I plan to spend time remembering James Chiles, the engineer who saved my life, James Bakhuyzen, the driver who lost his life, and my fellow passengers. Every one of us made it off the train that snowy March morning in 1993, so I can’t think of a better way to mark the day than by revisiting the site with gratitude.

Below, you’ll find a collection of my columns, posts, and essays published and shared during the 30 years since our train collided with a propane tanker on March 10th, 1993 in Michigan. It’s definitely messy stuff, full of discovery and growth and even some inconsistencies as I continue to learn details about the crash and process my feelings.

Writing always helps me process trauma. I hope this post offers some insight and inspiration to anyone who might need it.

Writing To Heal

Scroll down to read the five pieces I’ve written.

The first time I wrote publicly about the crash, I was a weekly opinion columnist for the Chicago Tribune’s Pioneer Press. The column was originally published by the Chicago Tribune on March 9, 2015.

The second time I wrote about the accident was three years later, on January 28, 2018. As you’ll see, I wrote much longer —and with far more detail.

The third time I wrote about the accident was in February 2018 for a piece I shared on The Moth Stage, just after the death of my younger sister.

The fourth time I wrote about the accident was on April 6, 2021. The piece was published by Invisible Illness (A Medium Publication), and it described the types of therapies I’ve used that have helped in processing the trauma.

The fifth time I wrote about the accident is today, pulling all these pieces together and creating this post. It’s intended to show how I’ve slowly grown in confidence to write about this traumatic experience.

It took me 22 years to finally write about the accident. Once I did, it became increasingly easier and more meaningful:

1993—The crash

2015—22 yrs between trauma & my 1st written piece

2018—2.10 yrs between my 1st & 2nd pieces

2018—1 month between my 2nd & 3rd pieces

2021—3.2 yrs between my 3rd & 4th pieces2023—1.11 yrs between my 4th & 5th pieces

A Written Journey of Healing

Piece #1

Chicago Tribune

March 9, 2015

TITLE: Sometimes Luck Is All In The Numbers

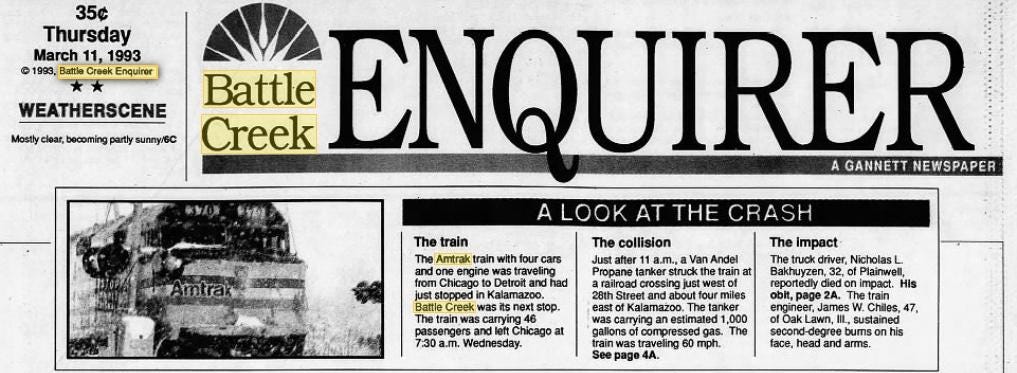

I was 24 years old on March 10, 1993, when I boarded the 7:30 a.m. Amtrak train in Chicago's Union Station. At 11:10 a.m., in Comstock Township, Mich., outside Kalamazoo, our train, traveling 62 mph, collided with a liquid propane tanker truck. The trucker did not survive.

Like so many previous trips to Battle Creek, my coworkers and I were scheduled to present advertising plans depicting critters peddling breakfast carbs to kids. Very, very important stuff this was, plus the annoying train always ran late.

The moment of impact forever plays in excruciating slow motion.

• A muffled thump from a distance ahead.

• An involuntary lurch out of my seat, knocking me to the floor.

• The expression on my boss's face shift from laughter to confusion.

• "Dan," I say, not at all a question. Perhaps a plea? A final statement?

• Screams erupt from up ahead.

• Dan's face, frozen, into a stare.

• A female voice.

• The smell of fuel.

• The realization I am screaming.

There is dead silence, then—though I'm crumpled on the floor—the brief sensation of whispers and free-falls, as if from a height. My clothes and hair lift briefly off my body then whip back against me in an invisible, crushing, and sustained blast of heat.

You've heard how lives flash before our eyes? It really happens. My life's "movie" lasted all of four seconds, but I saw everything. I was certain I was about to die.

At that time, The U.S. Department of Energy estimated an individual's risk of death by a propane shipment accident was 1 in 15 million—half the chance of death by plane debris hitting a person on the ground and 13,333 times more likely than death by a meteorite. And it's really no wonder I remember that heat: the same DOE study pegged the approximate combustion temperature of a propane tank rupture at 3,500 F.

When I realized the train was still moving, I tried to see beyond flames outside every window—including those tiny ones cut into the exit doors. As long as I live, I'll never feel as trapped as when those flames surrounded us. Only later did I learn how fortunate we were: our engineer, who sustained second degree burns on his upper body from the fireball, had the presence of mind to avoid braking until every car passed through—and beyond—the raging fire.

When we finally stopped, our car immediately filled with smoke. I can still feel the urgent, collective rush toward the doors, adrenaline surging as passengers pried open metal, still hot to the touch. We stumbled onto frozen land, smelling of panic, fuel and fear.

Within minutes, emergency personnel and reporters appeared, as breathless with their questions as we were numbed by shock. I zoned out, staring into the rounded, black sponge of a reporter's microphone, unable to describe the moment of impact.

A kind, local soul drove us to our client's headquarters, and we got there just in time for our afternoon meeting. I've never understood why we didn't just go home, but when you've just survived a fatal train accident, you're grateful to be anywhere.

Five years after the accident, I saw the movie "Sliding Doors," depicting two different ways a woman's life plays out, depending on whether she misses—or slides through—the doors of a train. I still love that movie and its evergreen message, that things always happen for a reason.

I am 46 years old, and this year I opened a writers' retreat 46 miles from the crash site. I am one of 46 people who survived the 1993 Wolverine Amtrak crash, thanks to a conductor whose name I never learned.

This column is dedicated to him.

My impression today: Holy cow. When I wrote that first piece, I was a relatively new journalist with a very newly-opened writers’ retreat in Michigan. Now, as I type this, 30 years after the crash and 8 years after that first column appeared, I’m in the midst of launching another writers’ retreat, this time in Arizona, a 5-day gathering supporting women as they embrace self-care and reframe difficult memories through Expressive Writing. Sometime tells me that’s hardly a coincidence.

Piece #2

ChicagoNow

January 28, 2018

TITLE: The 1993 Comstock, Michigan Amtrak crash. Reaching out, twenty-five years later, hoping to close old wounds.

I’m mailing the letters tomorrow, and I hope it’s the right thing to do.

Twenty-five years ago, on March 10, 1993, I was involved in an Amtrak crash in Comstock, Michigan. One man, Nicholas Bakhuyzen, was killed. Another man, the train’s engineer, James Chiles, received 2nd-degree burns on his face, head, and arms. Despite Amtrak’s initial reports, several passengers were also injured. All of us were changed forever.

And today, I finally wrote two long-overdue letters — one to Mr. Chiles, thanking him for guiding our train beyond the impact zone after we struck a tanker truck carrying 1000 gallons of compressed gas; the other to a relative of the driver of the truck.

The letters are not long. I did not allow myself to overthink as I wrote. Believe me, I’ve been thinking about these men for 25 years. I just needed to finally write.

It was an icy, snowy Wednesday when our train, Amtrak 350, left Chicago’s Union Station at 7:30 am. There were four cars behind the train’s engine, though I do not recall which of those cars I was in. I remember I was seated on the left side of the car, on the aisle. My boss at the time, Dan, sat next to me, at the window. I was twenty-four years old.

Bound for Detroit, our train had just stopped in Kalamazoo before making a stop in Battle Creek. It was there that Dan and I were to present work for our advertising agency.

According to court records, our train was traveling at 60mph around 11 a.m., four miles east of Kalamazoo, Michigan, when we struck Mr. Bakhuyzen’s vehicle. He’d been a driver for Van Andel L.P. Gas, operating a rig that was only 1/3 of its capacity full of fuel. The collision happened at a private grade crossing, intersecting the tracks and M-96, near milepost 139 in Comstock.

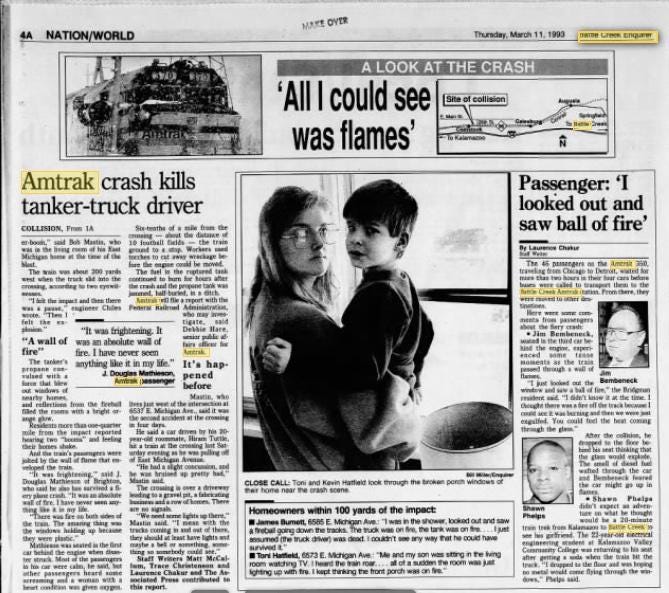

The crossing was known to be dangerous. At the time, there were no signals to alert drivers of oncoming trains. According to the Battle Creek Enquirer, our accident was the second at that crossing in four days.

Reports indicate that Mr. Bakhuyzen’s truck slid down an icy incline, causing him to lose control of the truck when his brakes locked up. We will never know the moment he saw our train coming, or what his thoughts were as he tried to stop his truck.

The train’s Pulse Event Recorder — similar to an airplane’s black box — indicates that our engineer, Mr. Chiles, had been sounding a warning horn for 1/4 mile before the collision. Mr. Chiles reported that he saw Mr. Bakhuyzen’s truck approaching the tracks and that he immediately sounded the train’s horn and applied the brakes, knowing that the truck was not going to stop. I can still hear that horn, which was active at the moment of impact.

When we hit the truck, I also heard the muffled sounds from the impact itself, followed by silence — and then the explosion. But it was the flames and the heat — not those sounds — I remember the most. The sensation of being surrounded by flames — without any idea of what was happening — is something I have worked for a quarter of a century to forget. I am now finally at peace with the fact that I will not.

The explosion blew out windows of nearby homes and businesses, shaking residences up to a quarter mile away. Upon impact, Mr. Bakhuyzen was thrown from his truck. He did not survive the crash. He was only 32 years old.

The engineer, Mr. Chiles, though injured and still applying the brakes, had enough sense to keep the train moving long enough to ensure all of the cars went through and beyond the crash site. Had he stopped too soon, some of us may have stopped in the midst of the burning wreckage. We finally came to a stop “six-tenths of a mile from the crossing — about the distance of 10 football fields.” (Battle Creek Enquirer, March 11, 1993, p. 4A).

After the crash, lawsuits were filed by the estate of the truck driver and one of my fellow passengers against the engineer and Amtrak. To this day, I have not read the judge’s final verdict, nor will any of the results matter to me.

What I know and care about is that the experience changed me in ways I never anticipated. I’m still understanding the scope of the impact, still learning how the cycle of PTSD and trauma affect a person, still trying to find meaning in such tragedy.

For years now, I’ve hoped to connect with Mr. Chiles and the family of Mr. Bakhuyzen. I’ve wanted to thank Mr. Chiles for doing what he could in those horrific circumstances, and to offer my condolences to Mr. Bakhuyzen’s family. Until recently, I’d often think about reaching out, but then I’d chicken out. I had no idea what I’d say. I didn’t want to upset these people any more than they might have one day been. And I was too afraid to open those doors. All I wanted to do was keep them shut.

But when I began to move through some unrelated struggles of my own, I adopted a two-word mantra to keep my chin up, and the memories of the Amtrak crash came back en force. My mantra, “Keep Going”, is in, a way, a metaphor for what the engineer, Mr. Chiles, actually did for his passengers that day. He kept going, even though it was painful. He kept going because it was necessary. And he kept going because it was the only thing to do.

I don’t know how Mr. Chiles did it, and I don’t know how he’s doing now. I sure would like to know, but he may not want to reopen any doors. And, honestly, who on earth could blame him?

I can’t imagine how Mr. Bakhuyzen’s family went on after what happened to him, but I’d still like to let them know that I’ve thought of him — and them — so often…and that I’m sorry.

I don’t know if it’s common to reach out to people in this manner, or if my letters will even open any doors. I don’t want to upset these individuals or reopen their old wounds for the sake of healing mine.

Like the collision itself, we can’t know everything that lies ahead. We can only react to the unforeseen as best we can. And sometimes, as I’ve learned, I just have to follow my gut .. and hold on, as it were, for dear life.

My impression today: I dug deeper and thought much more about others than myself. I continued to approach the subject from a journalistic point of view, which definitely helped. In doing so, I could approach the details with a level of detachment. Still, by learning more details, I was opening more doors to my memories and feelings, and they come tumbling out quite a bit in Piece #3.

Piece #3

The Moth Stage

February 28, 2018

I wrote and delivered this story on The Moth stage, when the theme of the night was “Transit”. It was my first time on The Moth stage, and I was a nervous wreck.

Piece #4

Invisible Illness (A Medium Publication)

April 6, 2021

TITLE: How EMDR and CBT Can Help to Navigate Trauma and Its Impact

Subtitle: Trauma has a way of staying (& keeping us) stuck in our minds & bodies. An in-depth look at how these life-changing tools can move us…

Two months ago, while driving on the highway, I spied an SUV five cars ahead, weaving erratically through the moderately heavy traffic. Immediately, I sensed the vehicle would crash. Ten minutes later, right in front of us, it did.

And it was in these minutes of hypervigilance — driving 75 miles-per-hour while anticipating (then finally witnessing) catastrophe — that I drew upon skills and tools I’ve learned — Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR). For me, the combination of these empirically validated psychological approaches have helped me process the trauma from my past and, even more significantly, navigate trauma as it occurs in real-time.

When I first notice the distressed vehicle on the highway, it is nearly 9pm. I’m driving southbound on Interstate 294 near Park Ridge, Illinois. The SUV, in the center lane, is drifting, braking erratically, speeding up and signaling lane changes that do not correspond to its unpredictable movements. I’m behind the wheel, and my boyfriend is in the passenger seat.

“My God,” I say, pointing toward the SUV just after we merge into the swift flow of traffic. “Look at that car. It’s ALL OVER the road.”

Though I can’t tell if there’s a man or a woman behind the wheel, it’s not hard to wonder if the driver is either under the influence or having an urgent, medical emergency.

Since the pandemic began, we’ve witnessed a sharp rise in speeding and dangerous maneuvers on highways, but this? This is different. This is a car veering and overcorrecting, repeatedly and miraculously missing concrete dividers and other motorists by inches.

Thirty seconds after spotting the SUV, we make the first of three emergency calls to 911. During each one, we’re transferred to the Illinois State Police. During our last call, we report that the car has crashed, and urgently request an ambulance.

Earlier that night

Earlier, on our way to the expressway, we approach a railroad crossing with its red lights flashing and its striped gates down. As I bring the car to a stop and watch the flash of a silver train zoom past, I hold my breath (as usual) as familiar memories fill my mind — remnants from the Amtrak crash I survived 28 years ago, in 1993.

Our train, which had left Chicago that icy morning, collided with a propane tanker near Comstock, Michigan. The impact killed the truck driver instantly. There were 46 of us on the train that day, and though some suffered significant physical injuries, others, like me, walked away from the wreck without a scratch, albeit with the deep and invisible wounds of trauma.

Our train’s engineer envisioned and accepted the impending crash long before anyone else. According to legal documents filed after the accident, he’d sounded the train’s horn in a series of desperate, prolonged warnings as he watched the truck sliding down an icy slope and directly toward the tracks on which we rode. In the years since the accident, I’ve often tried to imagine the stress and anxiety the engineer experienced in those moments leading up to the inevitable crash.

Surviving an actual trainwreck

I’ll never forget how it all happened so quickly — the sustained sound of the train’s horn, the deafening silence seconds before the fireball blasted through our car, the rush toward the exit after the crash. It was only then that, in my frenzy to get up off the floor and out of that smoke-filled, propane-soaked car, that I grabbed my work bag and my winter coat, though I don’t remember any of this. What I do recall is stepping into the icy daylight in my “smart” business suit, trembling, shivering, and sweating under the invisible cloak of shock.

What I couldn’t yet grasp was the impact of the impact. What I couldn’t yet know was how the crash would change me. The incident, which took less than one second to happen, would take decades for me to fully acknowledge, let alone comprehend.

The Science of Trauma

It’s been said that we hold on to the trauma in our lives, and as the title of Bessel Van De Kolk’s New York Times bestseller so aptly sums it up, The Body Keeps The Score. Science tells us trauma has a way of staying in our bodies and minds long after catastrophic events occur — a phenomenon now studied by many including the Traumatic Stress Research Program at the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH).

According to the program’s website, one of its many efforts focuses on the psychopathology related to trauma, including research on neurobiological, behavioral, cognitive, and other risk and protective factors after traumatic events to better understand and develop interventions for posttraumatic thinking.

The program explores the dynamic ways trauma can manifest — including how the brain adapts to and extinguishes fear and how the dynamic functions of memory acquisition, consolidation, and extinction are influenced by neurodevelopment, aging, and other factors in at-risk or symptomatic individuals.

And while this program validates and offers tremendous hope for trauma survivors, I’m not here to speak to the science. I’m here as a trauma survivor, and this is my story about how trauma keeps showing up, and what I’m doing to manage it.

Keeping Me In The Driver’s Seat: CBT and EMDR

Sitting in my car as the silver train rushes by, I take a few deep breaths as the crossing gates lift, then step on the gas pedal and continue driving toward the highway.

These days, the flood of memories from my train accident is far less severe thanks to my work with CBT and with a trauma therapist who introduced me to Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR).

What is CBT? How do you use CBT?

I’m not an expert in the practice, but in my experience, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is an approach that helps us overcome overwhelming or negative thinking patterns by breaking things down into smaller, more manageable parts. One real-world example is how I use CBT is in my training as a walker of marathons.

Before learning CBT, I’d tried unsuccessfully to complete a 26.2-mile marathon, but gave up at mile 16 feeling depleted, defeated, ashamed, and convinced that I’d “never” do another one. How’s that for negative?

After learning CBT and its many helpful tenets (about which I go into greater detail here), I cut myself some slack after that first disappointing marathon attempt and learned to set more realistic (and achievable) training goals. I’ve since completed my 2nd and 3rd marathons and am now training for my 4th.

With CBT, you learn to offer yourself compassion and grace for being human, moving through life with a clearer voice and stronger awareness of what is — and is not — within your control.

Since learning CBT, I’m better able to step out of those moments of paralyzing overwhelm and DO something to keep myself moving forward, whether it’s (among other things) challenging my thoughts, noticing my body’s reaction to situations, or reaching out for support.

What is EMDR? What does EMDR look like?

According to the 2013 World Health Organization, “[EMDR] is based on the idea that negative thoughts, feelings and behaviours are the result of unprocessed memories. The treatment involves standardized procedures that include focusing simultaneously on (a) spontaneous associations of traumatic images, thoughts, emotions and bodily sensations and (b) bilateral stimulation that is most commonly in the form of repeated eye movements.”

While I can’t say EMDR’s been easy, I can say, unequivocally, that it’s worked for me, and that it continues to help me manage the lingering impacts of trauma. Before EMDR, I’d sometimes have out-of-body experiences thinking about that train accident, to the point I’d find myself unable to function.

Something as benign as the sound of a distant train horn or the flashing of a crossing light or the sight of a speeding train might stop me — literally — in my tracks, and I’d be right back on the floor of that Amtrak car, praying that the flames would take me quickly. It wasn’t a conscious thought process, nor was it one I felt I could control. Trauma resided deep in my body, and until I finally addressed it, I didn’t know how best to name, validate, or process my experience.

For me, an EMDR therapy session looks very much like a “typical” session in my therapist’s office. She sits in an armchair. I sit across from her on a comfortable couch. Most of our activity involves conversation. The only thing that “looks” different is that I’m wearing a set of headphones and holding a pair of small, tactile pulsars in each hand. The headphones and pulsars are attached by thin wires to a small box my therapist holds (about the size of an iPhone), on which there are dials that allow her to adjust the volume in my ears and the speed of the vibrations in the pulsars. Believe me, the first time I heard about EMDR, it sounded pretty “woo woo” and “out there”. However, the pulses are gentle and soothing, and there’s nothing invasive about the experience.

Most of all, it works.

I close my eyes and listen to the rhythmic sound in my ears. It almost sounds like a ping pong ball in play, bouncing back and forth, though anyone can opt for other sounds, like a traditional “clap”, a “snap”, or various tones. Under my closed lids, I move my eyes back and forth to the sound. In my hands, I feel the pulsars gently alternating vibrations with each bounce.

The idea of EMDR is surprisingly simple. As my mind focuses on the external sounds and sensations, my therapist guides me (at my own pace) back to a traumatic memory, helping to put me right back in the moment. While some might liken this to exposure therapy, it’s different, in that the goal here isn’t to desensitize memories, but rather to reframe them. I’ve never been hypnotized, and I wouldn’t say that’s what this is (at all), especially since there are oftentimes I’ll stop to wipe my tears with a tissue or open my eyes and explain that I can’t “get into” my memory (usually due to fear) or that my mind has just trailed off on a random tangent (also likely due to fear).

And, we don’t just “dive in” and start talking about the traumatic event. Over the course of some therapy sessions, my therapist and I speak in general terms about the accident and other issues. Then, as I grow more comfortable sharing details, we work our way toward doing EMDR. Once I’m ready to face those intense memories directly, we continue talking about the event, with my therapist regularly asking me to notice what I feel in my body.

At first, when remembering the train crash, my body tenses and I can barely speak. I often dance around conversation of the actual crash — or to be more accurate, around my FEELINGS about the crash. But with my therapist’s support, I start our first EMDR session. Keeping my eyes closed, I picture the flames from the crash shooting above my head, and I hold my breath while fighting the urge to physically bolt. I give up after just a few seconds, but it’s a start, and she was there to witness me trying. I give myself credit for making the attempt, for taking a brave step — something I’m not wired to do automatically. This I learned through CBT.

For me, an EMDR session usually lasts anywhere between 5 to 15 minutes, with my therapist speaking in a soothing voice while witnessing any moments of my distress; these typically show up as a furrowed brow, streaming tears, hard swallows, or hand-wringing. Before long, I’m able to stop thinking about the ping-pong sound in my ears, and the movement of my eyes from left to right, and the vibrating sensation in my hands, letting my mind take me to the terrifying moments I’ve kept buried, including the terrifying, fight-or-flight desire to run and scream.

In the safety of my therapist’s office, though, I no longer feel the urge to run or scream. And the more I face the accident and allow the buried feelings to surface, the less I wring my hands or hold my breath when thinking about that day. EMDR helps me to see how my body keeps replaying its traumatic response, and that I have the power to break this fear-based cycle. EMDR allows me to re-experience the event without feeling re-traumatized, reminding me I am no longer in danger.

Subscribed

At first, when I allowed myself to think about the train accident, the most troubling feelings were the confusion and the profound sense of helplessness. But, by talking through these feelings, my therapist not only validated my emotions, but most importantly, helped me to reframe them. When I explained that I felt vulnerable and weak and powerless in the moments after the crash, my therapist nodded, then asked how I feel now, years later.

“Nervous,” I concede.

“What else?” she asks.

“Glad it’s behind me,” I say, “but still guilty.”

“You feel guilty. For what?” she asks.

“For having walked away without a scratch. Others were injured…or…killed,” I say. “I walked away. I don’t want to keep obsessing about it, but I do.”

“Were you not injured too?” she counters.

This. Is. Profound.

“You were injured that day, too,” she says, and with my eyes closed, I tilt my head.

“Well, yes, but not…”

“Not visibly injured,” she offers.

My eyes keep moving, left to right, left to right, in perfect time with the sounds in my ears and the vibration in my hands. I can’t see anything, but I feel seen. I feel heard. I feel movement all around me. I feel proof of life.

And then, perhaps the most important part of EMDR happens when my therapist asks, “What would you say now to Christine The Passenger as the crash unfolds?”

“What?” I ask, wrinkling my brow. “You mean, like, ‘Make sure you duck below the flames?’”

“I mean, looking back, what would Christine Now say to Christine The Passenger?”

This is the hardest work of therapy, when we don’t quite understand…and when we feel stuck. And yet, my eyes keep moving and the sounds keep ping ponging and the vibrations keep tickling my hands. And though my thoughts feel momentarily stuck, my body — sensing this ongoing, external, tactile momentum — feels prompted to keep going, to keep searching, to keep figuring this out and getting unstuck.

“What would I say to Christine The Passenger?” I ask, almost sarcastically. “I’d say ‘You’re about to crash into a propane truck and plow through an inferno…”

“and…?” my therapist asks.

“…and someone is going to die. And someone will be severely burned. And you’ll be thrown to the ground…”

“and…?”

“…and you’ll not talk about it with anyone because everyone will express gratitude that you didn’t get hurt and that you walked away without a scratch…” (by now, I’m crying, and my therapist is there to acknowledge these tears)

“and…?”

Left, right. Left, right. Ping, pong. Tap, tap.

“…um…”

Left, right. Left right. Ping, pong. Tap, tap.

“…and still, I was still terrified and I’ve been carrying flashbacks around for more than twenty years…” (more tears…and more acknowledgment by my therapist: “That must have been so hard to carry these feelings for so long, to not have that trauma acknowledged”)

“Yes,” I say.

Left, right. Left, right. Ping, pong. Tap, tap.

“and…?”

“…and I am still here…” I say.

“because…?”

“Because? Um… because…I survived.” This answer feels way too obvious, but it ends up being the answer.

“Yes,” she says. “You survived. So what does that make you?”

I catch my voice in my throat.

“A survivor?” I ask.

“That’s right,” she says. “You, Christine, are a survivor.”

And in this moment, instead of feeling guilty, I feel strong.

“You’re a survivor,” she says (prompting more tears from me), “and there’s no weakness or helplessness or shame in that.”

Left, right. Left, right. Ping, pong. Tap, tap.

“You’re right,” I say.

“Good,” she says. “And so, if you could talk to Christine The Passenger now, what would you say?”

“I’d say, ‘You will survive. You are strong. And when this is all over, you will definitely share your story.’”

Months later, as I sit in my car watching the silver Amtrak whiz by, I remember those feelings of empowerment. I am able to sit at a crossing gate and watch a speeding train go by without flashing back to the trainwreck for more than a moment. It seems CBT and EMDR have made a lasting difference in my life. And as I put the car in drive and resume our journey toward the highway, I have yet to appreciate how much these skills will help me in new situations — exactly like the one I’m driving us toward.

Subscribed

Back on the highway

“We need to call 911,” I say to my boyfriend.

Our first call goes through at 8:50pm, and we’re immediately transferred to the Illinois State Police. The call lasts 2 minutes, during which we’re asked for a plate number (which we’re too far away to see) and a detailed description (ditto).

When I explain to the officer that I can no longer see the SUV, he thanks me for the call and says he must take another. Though I’m disappointed, I hope the other caller is someone as concerned as me, someone with, perhaps, some more detailed information.

A few minutes later, I’m pretty sure I spot the SUV’s turn signal which has been flashing since I first spotted the vehicle. I’m still driving about 70 mph, but the SUV driver is far, far ahead of us. In less than a minute, though, we’re just two or three car lengths behind it. Still, before we can read the license plate, the vehicle accelerates like a rocket, driving on the shoulder, barely missing other vehicles. Again, we call 911, and get transferred to the State Police.

As I describe the vehicle and our current location, I’m shaking as I watch other cars avoiding the mayhem. Our second call, at 8:54pm, lasts just one minute, and though we’re assured that help is on the way, I just know something catastrophic will happen before help arrives.

The SUV’s driver, even more erratic now, comes to an almost complete stop in the middle of the highway, prompting everyone around us to suddenly brake. My boyfriend urges me not to get too close, and he’s right…though I don’t want to lose sight of the driver again. I’m now wondering if there are kids in the car. Is the driver suffering a medical emergency? How about the unknowing drivers on the road — will they be able to respond appropriately and quickly enough when this car gets near them? Why am I anywhere close to this individual? What are they capable of? How will a State Trooper ever catch up? What can they even do? Will help even arrive in time?

There are few words powerful enough to describe the ache of knowing catastrophe is iminent, but just as the train engineer sensed it that fateful day of the trainwreck, so, too, do I on this darkened highway, knowing the crash will come. Instinctively, my hands grip the wheel. I clench my teeth. I hold my breath. These are all physical manifestations of the nearly incomprehensible flood of emotions swirling through my anxious mind.

More and more cars around the SUV begin swerving to avoid being hit. I’m at once grateful to see others aware of the problem, yet fearful for those as of yet oblivious to this impaired driver. I want to flash my lights, scream, or blast a long and sustained horn as a warning. Experience has taught me, though, that this will not work.

Then, amidst a pack of drivers, the SUV slows again to a terrifying 25-30mph, only to accelerate and dart around other cars before zooming in front of the 18-wheeler in front of us.

One second later, the crash finally happens.

Invisible Impact

I don’t directly see or even hear the impact — but I sense that same, almost instantaneous and unmistakable muffled-yet-screechy, metal-on-metal slam, the one you really only know if you’ve been in (or around) a crash. And as I sense that sound, I see a bright flash, and then the plume of dust and smoke, followed by a brilliant glow of brake lights illuminating the inky night.

And there, I can now see, over on the right shoulder, is the SUV, fully stopped in front of the 18-wheeler, its front end completely smashed in and its shattered windshield pointed toward oncoming traffic.

Applying my brakes, I can’t help but say, over and over and over again, “Oh my GOD. Oh my GOD. Oh my GOD.” Following the 18-wheeler and several other vehicles, I guide my car toward the shoulder, my mouth covered by one hand, trying my best to remember how to breathe.

Subscribed

How to stop obsessive thoughts

We come to a stop and I turn on the hazards. The 18-wheeler is parked further up ahead. Between us on the shoulder, there are now 2 or 3 other cars — one of which is the smoking SUV. The flow of traffic, which, when the crash occurred had momentarily halted, has already resumed a brisk-yet-snakelike flow, avoiding glass and debris littering the road. There is no one behind my car.

“I KNEW IT,” I hear myself saying repeatedly — and I really mean over and over and over. “I KNEW this was going to happen. I KNEW it.” I felt angry…helpless…frightened…worried… unsure about the SUV driver’s condition, as well as any other drivers who may have been hit. With a shaking hand, I reach for the phone again, this time — 9 minutes after our first call — to request an ambulance.

At first, I’m too upset to speak, so my boyfriend initially talks to the Illinois State Police, describing exactly where we are. But then, I reach for the phone and tell the officer that we’d called twice before, and that emergency help is now urgently needed. The officer takes my contact information and tells us not to wait on the side of the road. “We’ll call you if we have questions,” he says.

My first instinct is to leap from my vehicle and run to the smoking car, to be with the driver until help arrives. As my fingers fumble for the door lock in the darkness, I can’t see any flames, yet they’re still present in my mind — because that’s how trauma works.

This auto crash has triggered me, mixing up concerns about the SUV driver with thoughts of my train accident. I can see both of us in my mind, trapped, surrounded by flames.

Turning to my boyfriend, I say something to the effect of, We can’t just sit here. We need to help! In this moment, it’s hard to know what’s pulling me more to that smoking vehicle — the SUV driver or memories of Christine The Passenger.

In my mind, I can even sense the smell of leaking fuel — not of gasoline, mind you, but of propane from the tanker truck that crashed into our train 28 years ago. I can feel my body — and especially my legs — fighting against two forces: the need to run, and the urge to throw up. My reactions, though based in my thoughts, feel physical in nature.

But then, as I reach for the handle of the car door, I stop.

Thanks to years of practicing CBT, my mind figures out how to pull itself away from these intrusive thoughts of my past. Though I’m still shaking, I’m back in this moment. Looking around, I assess how dangerously close we are to the flow of traffic. As the State Trooper just said, we’re not in a safe place. Getting out of the car would be a very bad idea. I also realize other little details, like not even knowing where my COVID-19 mask is at the moment.

In the moments immediately following my train crash, I’d felt trapped and helpless and terrified and confused. Even though I’d been with a coworker, I felt alone and utterly terrified. Then for years after that, I couldn’t be in — or even near — a passenger vehicle like a train or a plane or a cab or my own minivan without scanning for exits and regularly flashing back to my escape from that propane-soaked train car. The mere suggestion of being near these kinds of vehicles triggered me. Seriously, just ask my family (especially my teenagers when they were learning to drive) — I was a horrible, horrible passenger, and they suffered as a result of my anxiety.

But now, sitting here on the side of the road, even though I sense some frighteningly familiar feelings like chaos, helplessness, urgency and a physical desire to run, this time, my intentions and desired destination are completely different. This time, unlike the aftermath of the train accident, I feel the need to run toward — not away from — danger. And this, I know, is a clear sign I’ve evolved.

Interrupting trauma’s lasting impact with CBT

In my car, I keep applying CBT skills, practicing breathing and checking in with where I am physically. I remind myself I’m okay. I’m behind the wheel. I’m in charge of my own situation.

One of the most helpful things I’ve learned from CBT is to use “and” statements. I repeatedly remind myself that I’d already known what was coming…and that it actually happened. Unlike the train accident, which I couldn’t see coming, I saw this scenario play out before it happened. Yes, I was still shocked by it, and I also felt my instincts doing exactly what they were designed to do. My instincts had protected me, and in the process, allowed me to try to protect others. I remind myself I’m anything but trapped or helpless. I remind myself I can feel scared and worried and also safe and wise and strong.

Whereas two minutes earlier, I’d felt compelled to run from my car and help this individual, I now find myself driving away from the scene, driving away from the smoking wreckage.

As we pass it, I have to avoid the twisted pieces of metal and the burned pieces all around it. Looking quickly at the SUV, I can see the hood smashed in and the windshield shattered. Later, my boyfriend tells me he thought he saw someone with a baseball hat, slumped over the steering wheel.

We barely speak for the first 10 minutes after leaving the scene. Part of me expects a call from the State Police, but to this day, two months later, we haven’t heard from anyone.

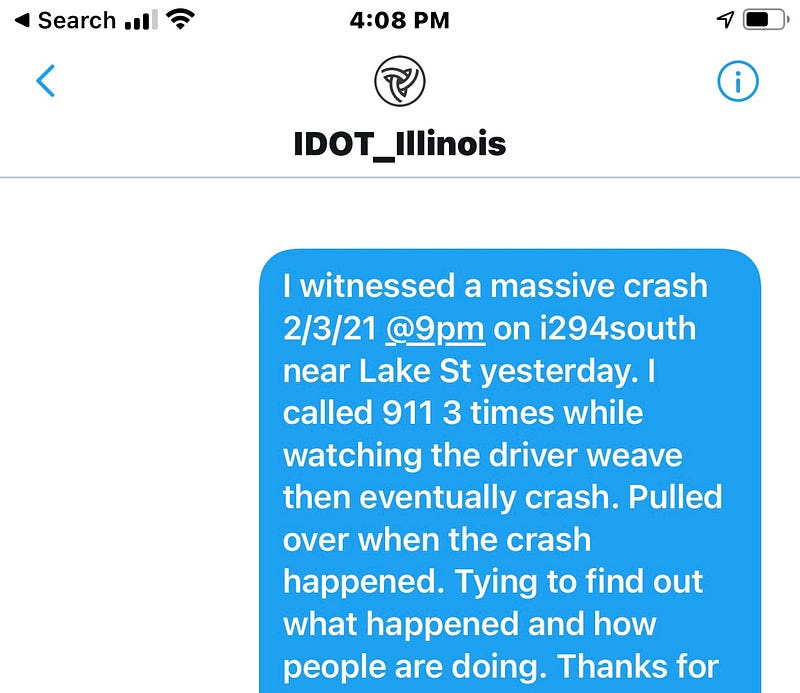

That night, I find myself Googling obsessively, trying to learn anything about the incident or the driver or the aftermath. My boyfriend finds the one-and-only Illinois Department Of Transportation Tweet about the incident, and I reply to it immediately:

The next day, I send a DM to the Illinois Department of Transportation:

Aftermath

I have come to accept the unlikelihood that I, a bystander, will learn anything more about the SUV’s accident than what I’ve already seen (which is more than most) and that’s okay.

I recognize that the “busy work” I engaged in immediately following the accident — researching, reaching out, Googling, trying to learn everything I can, trying to “do” something — made me feel like I was being productive. It was my way of distracting myself from my feelings about witnessing the accident, turning outward rather than sitting with and processing the discomfort.

Writing to heal

And now, as I type, I unwrap these feelings and lay them out as words for you, putting my heart on the page. And I remind myself this was yet another crash beyond my control, and that I — and we all — must keep moving and keep going forward.

Now, you might reasonably say, “But wait! You clearly haven’t let this go! You’re writing obsessively about it right now!” And, you’d be partially right. I am writing about it, and that’s what helps me process it. As a writer, I find meaning and healing through writing. I’m not an expert in CBT or EMDR, but I’m an expert at how those tools impact my life. And the process of documenting my experiences offers me a deeper understanding of where I’ve been and how far I’ve come. These are the ways I cope.

Releasing helplessness

The most important thing I’ve learned from trauma therapy is how to recognize those all-too-familiar feelings of helplessness, and to consciously release them by identifying my points of strength. If you’ve ever experienced trauma, you know the feeling of being blindsided…of having the rug ripped out from underneath you…and of having to pick up the pieces. Those awful feelings are hard to shake, and it’s easy to slip back into hypervigilant, defensive, protective, emotional patterns. They may not even fit the circumstances, but they’re familiar and, in a slightly twisted and frustrating way, even comfortable. This, to me, is the essence of PTSD: gaining a false sense of comfort from previous and/or familiar discomfort.

When you experience trauma, it’s like your boat’s been terrifyingly and unexpectedly rocked, so to protect yourself, you replay and re-examine that boat-rocking over and over and over again, trying to understand and discern what caused it or what you missed, all while convincing yourself the boat will likely rock again, even when you’re in calm waters. The mental space PTSD takes up is crazy-making, actually. Growing up, I couldn’t understand why my grandfathers, who’d served in WWII, never spoke about their experiences. Now, I can only imagine the horrors they saw or the thoughts they tried to manage or the “normalcy” they tried so hard to achieve.

What does PTSD “look” like?

While every person and every situation is different, I believe the aftermath of trauma can sometimes be worse than the traumatic event itself. Individuals suffering from PTSD might look cornered … or “normal”… or perseverating … or shut down … or overreacting … or pulling away … or lashing out … or even completely unaffected. There is no “one way” that PTSD looks.

Thanks to my familiarity with EMDR, I was able to access my Christine Now voice and remind myself I’d been more than “in control” during those 10 harrowing minutes that felt so helpless in the moment. I’d tried my best to help someone in need. I did the best I could in those awful circumstances.

Still, I wonder about the driver and all those who shared the road with us that night. I wonder how everyone’s doing, and if they’re able to process things. It’s my hope they all might find the support and understanding they need to process their experiences — and to keep moving beyond that crash.

Trauma Resources and Links

Explaining the Various Impacts of Trauma

For more information, the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) offers an outstanding explanation of the various impacts of trauma, including triggers, flashbacks, and the most common experiences and responses, such as emotional dysregulation, numbing, dissociation, somatization, hyperarousal and sleep disturbances, cognitive errors, excessive or inappropriate guilt, idealization, and intrusive thoughts and memories.

EMDR

Shapiro F. (2014). The role of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy in medicine: addressing the psychological and physical symptoms stemming from adverse life experiences. The Permanente journal, 18(1), 71–77. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/13-098

Traumatic Stress Research Program, National Institute of Mental Health

My impression today: Ummmm that piece was WAY too overwritten and meandering (CRINGE), but that’s okay. That’s kind of the point when processing trauma. We see what shows up and allow space for things as they rise to the surface. I’m happy to see that I did more than just focus on that single event. In this piece, I wrote about the crash in the context of some other life experiences, and (if you look hard enough), I try to offer insights and information meant to help others.

Piece #5

Substack

March 8, 2023

You’re Currently Reading Piece #5

TITLE: How I'll Mark the 30th Anniversary of the 1993 Comstock, Michigan Amtrak Collision

Subtitle: It's a way I never could have imagined.

My impression today: Healing is so clearly a journey, not a destination. I’ve worked hard in these past 30 years to face, unpack, and find meaning in my experience. I was 24 when I survived the crash. I’m 54 now, grateful for every day I have to help others work through their own memories of trauma and upheaval.

Follow Christine at www.christinewolf.com

SURVIVOR!!! ❤️ 😢